Lander University faculty members use artificial intelligence tools in their classrooms to prepare students for a world in which AI technology is advancing at high speed.

From speech classes to marketing to teacher education and beyond, Lander students are using various AI tools to supplement their learning. The University has also provided a course for students to learn more about AI itself and how it affects language and writing.

Artificial intelligence is all around us and its forms are wide-ranging, from chat bots like ChatGPT, which use large language models that rely on algorithms and a preset set of data to generate information, to facial recognition software, to predictive text in emails or word processors. There are also AI image generators, pulling from existing data to produce images based on prompts.

Dr. Cherie Rains, Lander associate professor of marketing, has introduced AI to her students, primarily to her social media marketing class.

She mentioned students will be asked in job interviews if they have ever used AI and what tools are out there. If they haven’t and can’t answer that question, she said, it will put them at a disadvantage.

They began with an exercise in how not to use AI, partly dealing with academic integrity but also to prepare for life after college. In one example, she gave her students data and asked them to find the source of the data to be sure they can cite it. As the students came to find out, that source didn’t exist – it was data fabricated by ChatGPT.

Numerous classes at the University have had students use AI tools for content generation.

Rains’ classes have used ChatGPT and Canva’s text-to-image tool to create social media content. That’s hopefully a way they will use it out in the field, she said.

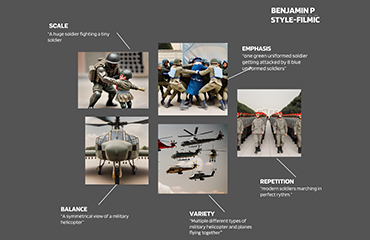

She worked with Dr. Kristen Applegate, assistant professor of art, on the text-to-image piece. Applegate also had students in her art appreciation use Canva’s text-to-image tool to generate art for an assignment. In that course, she teaches the elements of art and principles of design – things like emphasis, scale, repetition and balance.

She wanted the students to be able to come up with images using text prompts that demonstrated those elements, so she had them create five visually cohesive images based on text.

In the College of Education, Dr. Rachel Schiera, assistant professor of education, has used AI in her teacher education courses to develop lesson plans.

She said around the time that ChatGPT got big, students began asking questions about it, so she had students in her STEAM (science, technology, engineering, art, mathematics) methodology course generate a lesson plan using the technology.

“I was like, ‘It’s as simple as this. Just put into ChatGPT “make me a lesson plan for STEAM,”’” she said.

This past semester, she did a project where students crossed standards and a real-world problem, mixing a lesson about making buildings hurricane-proof with the “Percy Jackson and the Olympians” young adult book series. Cross-curriculum lesson planning is already complex, Schiera said, and using AI aided the students.

Student reaction to using generative AI in their courses varies. Schiera said she got a whole range of feedback.

“I do get students who are completely against its use and feel like it’s cheating. They don’t want to use it, and we have faculty who feel the same, and that’s fine if they want to think that,” she said. “But I do require that they use it, so I say, ‘I want you to get output. You don’t have to use the output, but I want you to interact with the tool.’”

She said some students who are more pressed for time are thankful for it, while some who are resistant to large language models like ChatGPT are more comfortable with teacher-specific AI tools, like Magic School.

Rains said reactions in her class have run the gamut from “Wow, that was great and I learned something I’ve never done before,” and “I see the need for it in the field,” to “Wow, that was kind of creepy and I didn’t like it.”

Applegate said her assignment was well-received and she asked her students how they felt about AI in education generally.

“There were some funny answers like ‘I really enjoyed this, it was a whole lot of fun, but I don’t really trust AI,’” she said.

The use of AI in classrooms doesn’t stop at generative AI.

Monique Sacay-Bagwell, requires students in her public speaking courses to use AI software called PitchVantage to practice and get feedback on their speeches.

“For whatever reason, a lot of time students will wait until the very end, sometimes minutes before the class starts, to actually practice their speeches,” Sacay-Bagwell said. “They spend a lot of time writing the speech but sometimes that doesn’t happen in a timely fashion, so they’re pressed for time. They think that giving a speech is just writing something down, standing up and just reading it.”

That’s far from the case. While she wasn’t seeking out a solution, Sacay-Bagwell said one fell in her lap when the company contacted her and she realized it might solve the problem of getting students to practice.

PitchVantage allows students to choose a room size to practice in and select their audience members. While they deliver their speech to an artificial audience, the avatars are expressive. If uninterested, they look at their watch or glance around the room, but if they’re interested, they will smile or lean forward. The software will then provide students with feedback, evaluating their delivery style and how they organized their thoughts.

Sacay-Bagwell said she has seen growth overall in her students’ speeches and said there is better consistency in how they deliver speeches. When students purchase the software, they have access to it for six months and can use it for other purposes, too. There’s an AI job interviewer that will give practice interviews, and Sacay-Bagwell said she has had former students use PitchVantage for that.

Along with exposing students to AI in classes, students have also had the opportunity to face the question of AI head-on through a course called “Writing in the Age of AI,” which was offered in spring 2024 and taught by Dr. Sean Barnette, professor of English.

The course was a seminar-style class, full of discussion. The class read articles and a book about AI and language. Students also had to choose a book to read that had nothing to do with AI or with writing and give a presentation about how it can add perspective to discussions about AI.

Barnette said one of the things that surprised him coming into the class was how little the students understood about how AI worked.

“All of them were assuming that ChatGPT is searching the internet,” he said. “Because their framework is based on interactions with Google and they feel that you interact with Chat GPT more or less the same way: you put in a query or a prompt, and then you get something back. And so, they were assuming that it was working that way.”

Barnette said he sees people who are panicking while others treat artificial intelligence with an almost messianic reverence.

“I think one of the things that this class is really valuable for was saying, ‘Well those two extremes are probably both short-sighted. Let’s sit down and consider this a little bit more slowly so that we can decide where we want to be cautious, where we want to resist, and where this is a tool that actually can help us in a useful way,’” he said.

Carly Rogers, a junior English major from Simpsonville, said she took the course because she had concerns about her own job security, since she has a professional writing focus with her major. She also had ethical questions as a philosophy minor.

She said her viewpoint changed in the class from a fear of the systems themselves, to a concern over the motivations and actions of the people creating them.

“I do think that the biggest thing is don’t panic,” Rogers said.

“I would say that whether you are for or against using AI in your work, there’s no reason to panic about where it will lead our future careers, where it will lead the job market, where it will lead the economy, because as all new technology has been introduced, there have been solutions and accommodations. Sometimes that doesn’t benefit everyone, but it’s not like that’s anything new and it’s something we can be prepared for.”

Sacay-Bagwell pointed out that people use AI every day, even if they don’t realize it, and that’s going to become more and more true.

“Studies are showing that there’s certain industries that are threatened with AI or that there are still a lot of unethical things about AI. We can’t ignore that, so I think that it’s important for a university to teach students first of all what kinds of AI tools there are so that they are prepared to use them,” she said.

“It’s just such a fast-moving industry and there’s no limits to how big it can get. There’s no cap on this except resources and the intelligence of the person that’s creating it. I think it’s vital they use it,” she said. “It’s vital that all students have access to it, but we’ve also got to understand they already have and in some cases already have far more sophisticated access to different AI than we do.”

Schiera said AI is going to accelerate the pace that humans communicate at.

“But we have to know how to use it, we have to understand how to assess the output. We have to understand what these tools are, what they can be used for, concerns around security. All those things, we have to understand,” she said.

“We can't understand them if we don't interact with them.”